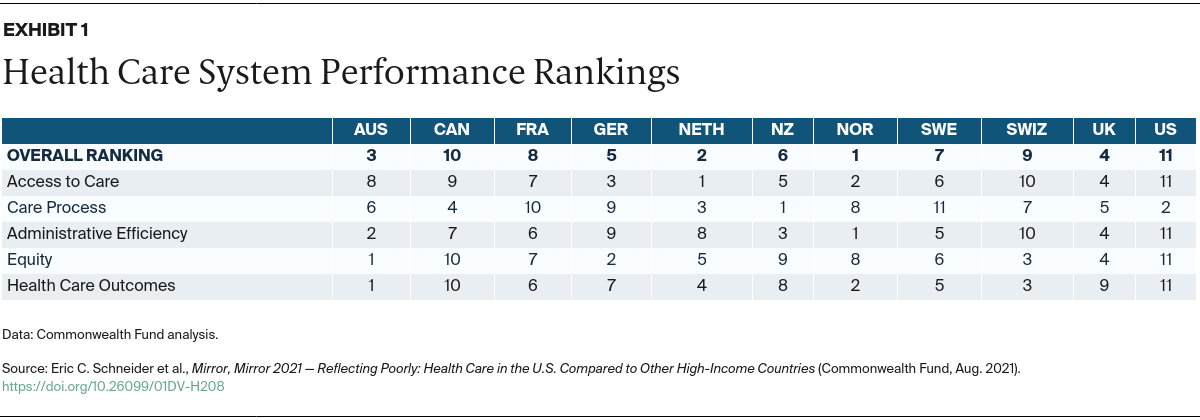

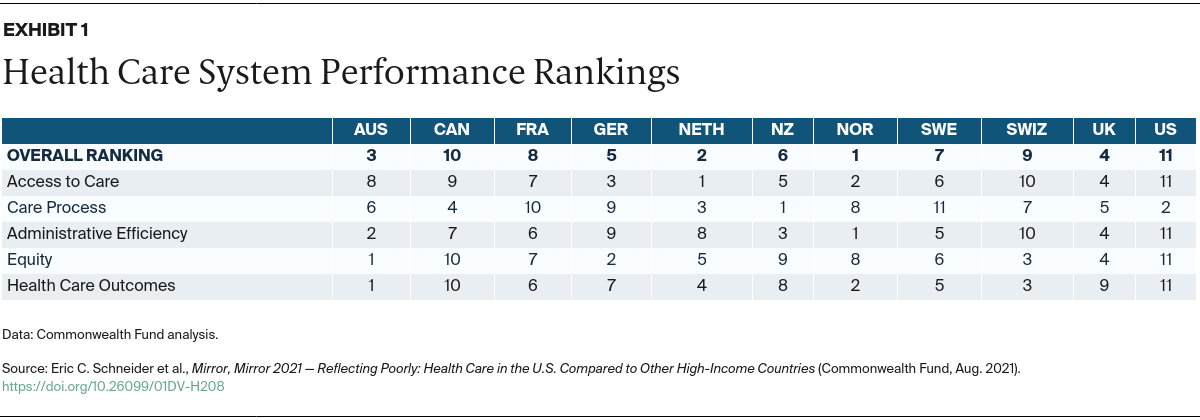

The U.S. health system trails far behind a number of other high-income countries when it comes to affordability, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes, according to a new Commonwealth Fund study. Using surveys and other standardized data on quality and health care outcomes to measure and compare patient and physician experiences across a group of 11 high-income nations, the researchers rank the United States last overall in providing equitably accessible, affordable, high-quality health care.

The report, Mirror, Mirror 2021 — Reflecting Poorly: Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries, shows that getting good, essential health care in the U.S. depends on income — more so than in any other wealthy country. Since 2004, the U.S. has ranked last in every edition of the report, falling further behind on some indicators, despite spending the most on health care.

Half (50%) of lower-income U.S. adults reported that costs prevented them from getting needed health care, compared to a quarter (27%) of higher- income adults. In the United Kingdom, only 12 percent of people with lower incomes and 7 percent with higher incomes reported financial barriers to care.

Remarkably, a high-income person in the U.S. was more likely to report financial barriers than a low-income person in nearly all the other countries surveyed: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K.

Norway, the Netherlands, and Australia were the top performers overall. In the middle of the pack were the U.K., Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, and France. Switzerland and Canada ranked lower than those countries, although both still performed much better than the U.S.

Among the 11 nations surveyed, the U.S. is the only one without universal health insurance coverage. Other research suggests that the U.S. spends less than other high-income countries on social services, such as child care, education, paid sick leave, and unemployment insurance, which could improve population health.

Additional report findings related to the U.S. include:

David Blumenthal, M.D., Commonwealth Fund President

“What this report tells us is that our health care system is not working for Americans, particularly those with lower incomes, who are at a severe disadvantage compared to citizens of other countries. And they are paying the price with their health and their lives. To catch up with other high-income countries, the administration and Congress would have to expand access to health care, equitably, to all Americans, act aggressively to control costs, and invest in the social services we know can lead to a healthier population.”

The authors say there are a number of lessons for the U.S. that could inform efforts to attain better and more equitable health outcomes:

Eric C. Schneider, M.D., Commonwealth Fund Senior Vice President for Policy and Research

“This study makes clear that higher U.S. spending on health care is not producing better health especially as the U.S. continues on a path of deepening inequality. A country that spends as much as we do should have the best health system in the world. We should adapt what works in other high-income countries to build a better health care system that provides affordable, high-quality health care for everyone.”

Reginald D. Williams II, Commonwealth Fund Vice President for International Health Policy and Practice Innovations

“Mirror, Mirror continues to demonstrate the importance of international comparisons. It offers an opportunity for reflection by health care researchers and policymakers, and the evidence base to learn from other countries and their approaches to improving health system performance for people.”

The 2021 edition of Mirror, Mirror was constructed using the same methodological framework developed in consultation with an expert advisory committee for the 2017 report. 1 Another expert advisory panel was convened to review the data, measures, and methods used in the 2021 edition. 2

Using data available from Commonwealth Fund international surveys of the public and physicians and other sources of standardized data on quality and health care outcomes, and with the guidance of the independent expert advisory panel, the authors selected 71 measures relevant to health care system performance, organizing them into five performance domains: access, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes. The criteria for selecting measures and grouping within domains included: importance of the measure, standardization of the measure and data across the countries, salience to policymakers, relevance to performance improvement efforts. Mirror, Mirror is unique in its inclusion of survey measures designed to reflect the perspectives of patients and professionals — the people who experience health care in each country during the course of a year. Nearly three-quarters of the measures come from surveys designed to elicit the experiences of the public and primary care professionals with their health system.

The method for calculating performance scores and rankings is similar to that used in the 2017 report, except that the authors modified the calculation of mean performance scores to address the outlier status of the US on several measures.

For each measure, the authors converted each country’s result (e.g., the percentage of survey respondents giving a certain response or a mortality rate) to a measure-specific, “normalized” performance score. This score was calculated as the difference between the country result and the group mean (after excluding the U.S. as described below), divided by the standard deviation of the results for each measure. Normalizing the results based on the standard deviation accounts for differences between measures in the range of variation among country- specific results. A positive performance score indicates the country performs above the group average; a negative score indicates the country performs below the group average. Performance scores in the equity domain were based on the difference between the two income groups, with a wider difference interpreted as a measure of lower equity between the two income strata in each country.

For each performance domain, the authors calculated a mean performance score for each country based on the performance measures in the domain. A standard statistical approach identified the U.S. as an extreme outlier on some measures in several domains or subdomains (affordability, preventive care, equity, and health care outcomes). To avoid outlier bias and for consistency, the U.S. was excluded from the calculation of the mean domain and overall performance scores. Then each country was ranked from 1 to 11 based on the mean domain performance score, with 1 representing the highest performance score and 11 representing the lowest performance score.

The overall performance score for each country was calculated as the mean of the five domain-specific performance scores. Then, each country was ranked from 1 to 11 based on this summary mean score, again with 1 representing the highest overall performance score and rank 11 representing the lowest overall performance score.